Home » Rabinowitz Esteron Yaakov Kopel

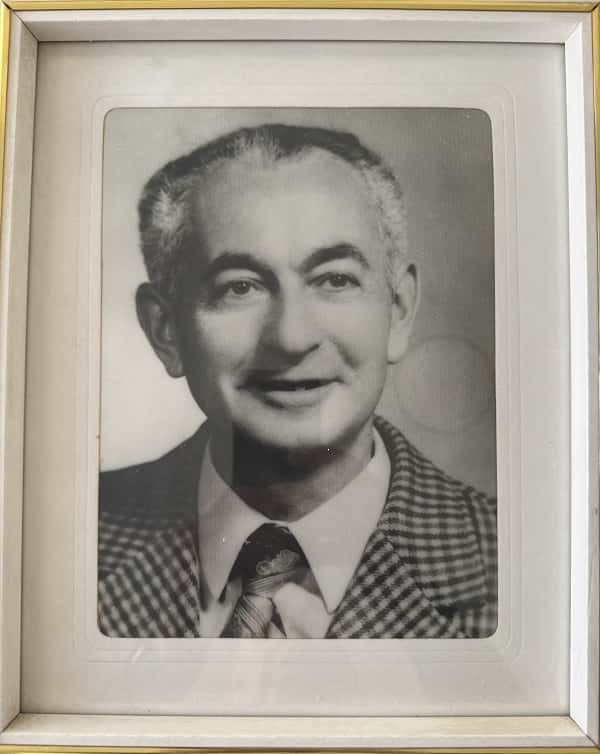

These memories of Hrubieszow were written by Yaakov-Kopel Rabinowitz, the youngest son of Aharon and Esther Rabinowitz, and the brother of Moshe and Yoel. Yaakov-Kopel, the sole survivor of his family, changed his surname to Esteron to honor his parents, and named his eldest son Aharon and his youngest son Yoel. Yaakov-Kopel was born in March 1917 and passed away in October 1994.

In these notes, I wish to document a few events leading up to the outbreak of the war. These pages are dedicated to the memory of my family members who perished in or outside of our hometown.

During the destruction of the ghetto in town, a rumor spread that the ghetto in Sokal still existed and people were allowed “to live.” Some townspeople attempted to sneak in, despite the obstacles, even against the wishes of the local Jewish community. My brother Moshe, z”l, smuggled our parents there in a horse-drawn wagon, but the Nazis bomed the cellars and bunkers of the ghetto, preventing their escape and killing many people, including my parents, Aharon and Esther. This happened a day before Shavuot Eve in 1942, as recounted by our neighbor Rosa Zilbermintz.

On the seventeenth of Kislev that same year, the Nazis led my brother, Yoel, z”l, and his close friend, Yokel Brand, z”l, along with several hundred townspeople, to the cemetery and ordered them to dig their own graves. They tried to resist, hurling insults at their killers, and were shot with dumdum bullets that shatter bodies. Yoel and Yokel died as heroes, inseparable in life and death. Shlomo Brand, Yokel’s brother, told me their story. The German murderer Ebener carried out his heinous plan after first sending them, along with thousands of others, to the Belzec Extermination Camp. While they managed to jump from the train, overcoming the sealed railcars (my brother sprained his leg and hid for a time with a Polish farmer outside the city), they were eventually captured and murdered.

My brother Moshe, z”l, later perished in the Leitmeritz Concentration Camp in Czechoslovakia at war’s end. When the Germans occupied our city, he was in Lviv. But for some reason, when war broke out between Germany and the Soviet Union in 1941, Moshe, Michael Finger, Chaim Zilberstein, and others decided to return home. This is the moment to mention what Moshe said in Polish when the Soviets were densing freight trains with refugees from Poland to the Russian Steppes all the way to Siberia: “Young Mr. Finger, you’ll see—we’ll envy those being taken to Russia.” Sadly, he foresaw what was to come.

Michael Finger (now Drori) told me that for a while in the ghetto, he worked with my brother, who was a pharmacist at the Jewish hospital on Lubelska Street. During those terrible days, my brother asked Michael to teach him Hebrew. Today, we marvel at his desire to learn.

My sister-in-law Dora Ilani, now in Israel, told me that the “aktions,” including the death marches and deportations, began as early as 1939. Our town was among the first to suffer German persecution, and even though the news reached Warsaw, people didn’t want to believe the “rumors”.

The Dror Freiheit Youth Movement (a Zionist-socialist organization) sent girls to gather intelligence. Once, Lonka Kozybrocka, who had a gentile appearance and Aryan papers, arrived in town. Sadly, in June 1942, she was caught in Małkinia, imprisoned in Warsaw’s infamous Pawiak prison, then sent to Auschwitz. Her Jewish identity remained hidden until she died as a resistance heroine in March 1943. Polish inmates laid wreaths on her grave, which were later burnt and destroyed. Her brother David Brodsky, who managed to escape the horrors to the United States and then to Israel, told me her story.

My father, z”l, ensured that his three sons received both Jewish and general education. He was an educated man. He once told me how, after World War I, a library named after I. L. Peretz was founded at the corner of Staszic and Rynk Street, where carters waited with horse-drawn wagons. He and his good friend Y. D. Mitlpunkt, a Yiddish writer, were among its founders.

My father championed Hebrew literature alongside Yiddish; after much effort, Hebrew books began to join our shelves. I remember him as a devout yet enlightened man, traditional, educated, progressive, and clean-shaven. His friends and colleagues were Jews, Russians, and Poles alike. Even though our economic situation was comfortable during my studies, my father lived modestly and asked little of life.

My mother, z”l, from the Eisen-Kopel family, was beloved by all. Her aristocratic beauty and humble manner made her one of the city’s most admired women. She was part of a women’s charity led by the wife of Chief Rabbi Wertheim. She also secretly provided food to needy neighbors and hospital patients. One of whom was Avigdor, known as “der vaser tregger” (meaning the water carrier), a lonely, elderly, deaf man with a white beard who carried buckets of water on his shoulders all day. My mother felt great compassion for him and treated him with hot meals, and later cared for him in the hospital when he fell ill.

I still wonder to this day – would my Polish friends have helped me during the war? As a boy, I used to do my homework at the home of Tushik (Antoni) Krasnopolsky; his parents welcomed me with open arms. Yet after the war, old Krasnopolski admitted that one of his sons had collaborated with the Germans. This son was supposedly my “best gentile friend.” I hope I am wrong, but who can say? Not long ago, I heard from Shlomo Brand, a partisan commander who visited our town after the war, that he met the elderly butcher Krasnopolsky. The latter told him that the Germans had taken his young son (Tushik) to the Majdanek Extermination Camp near Lublin. His fate remained unknown. Indeed, I did not trust those friends and escaped from the abyss. There were no Righteous Among the Nations in our town. There was only one known case of an attempt to save Jews — by Professor Lucjan Szydłowski, who was one of the leaders of the Polish People’s Party and a supporter of the Jews. He hid his good student, Sarah Zilberminz, and her family in his home, but she was later murdered.

On the other hand, two teachers at our school were known for being notorious antisemites: Professor Zalewski, the Polish teacher, and Professor Dovik (Gibben), who taught history and was my own homeroom teacher. Jewish students from other classes complained that Dovik graded them unfairly. In my opinion, the school administration was generally fair, and the grades were also fair. Two Jewish teachers taught at our school: Professor Baumgarten, who taught Latin and endured antisemitic harassment, and Mr. Oregon, our Judaism teacher (we studied the Bible in Polish, as ancient Israel’s history). Outside regular classes, there were cultural activities, including lectures, dances such as the polonaise and waltz, and classical music performed by our school’s chamber orchestra under the direction of Mr. Cibulski. Jewish students played key roles: Frank Peretz, Ynetza Apple (first violin), Zuza Waksman, and Chaim Reiter.

In 1933, the influence of the Nazis began to rise in Poland. Despite the bans, Polish students joined extremist Nazi groups and stood guard (“picketed”) outside Jewish shops, preventing Poles from buying. Even more so after Prime Minister General Składkowski declared a boycott on Jewish businesses, and anti-Jewish chants began ringing through our school.

The pogrom in the town of Pshityk and other antisemitic incidents had a substantial impact on our mindset. A relatively large group of Jewish gymnasium students joined Hashomer Hatzair. Once a week, we went to the clubhouse, where we sang and danced the Hora. We listened to lectures by our excellent counselors, the late Yosef Mermelstein, z”l, and Shike Borowicz, (now of Kibbutz HaMa’apil).

One day, out of the blue, we were summoned to the office of the school principal, Toporowski. He ordered us to cease all activity outside of school. Even before that, we had heard that our friend Chaim Reuter had been questioned about our involvement in the Zionist movement. After finishing high school, much more painful experiences awaited us.

In 1937, I enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the University of Warsaw, named after Józef Piłsudski. Soon, a regulation was mandated that required separate seating for Jewish students. They were called “ghetto benches.” About twenty of us refused to sit on these benches on the left side and instead stood in the back. A professor named Jara declared, “Those who wish to study law and justice must not violate regulations,” when antisemitic students started to jeer. We marched out, and some Poles chased us, yelling slurs and insults. All of a sudden, they drew sticks with razor blades from underneath their coats. We started running without even taking our coats. They got to one of us and wounded him, but luckily it was not serious. The police, bound by university autonomy laws, did not intervene in riots within the university. The antisemitic students from the “phalanges” stood watch outside Jewish bookstores in Warsaw. There, they felt the force of the Jewish porters’ strong arms. In our town, too, the Polish thugs occasionally experienced the strength of the Jews, porters, butchers, and simply tough men. There were no mass pogroms carried out by the Gentiles in our town, but violent incidents did occur from time to time. I remember a tragic case when Osher (Asher), the son of the painter Leib Shennol — a man with a long white beard — was stabbed to death by a drunken Pole. Sometime later, the murderer was killed by a group of avengers.

By 1938, I could no longer attend university lectures and left the capital. I came to Chełm, where I met my future wife, Genia, daughter of the late Yosef and Sarah Brener. When the German brutes invaded Poland, my two brothers and I fled our hometown and became refugees. My brothers later returned to Hrubieszów; I remained in Lutsk under Soviet rule in “Western Ukraine.”

There was a known story about a poor couple in the 1920s, whose wedding took place in a study hall across from the Great Synagogue. Suddenly, in the middle of the ceremony, the floor collapsed. A bottomless pit opened up—like in an earthquake—and the young couple and the guests fell in. Their fate remains a mystery to this day. People saw it as the work of the devil, who must be driven out of the city, and such things did happen. The pit remained open for many years, and we, as young children, were afraid to walk past it. There were other tragic incidents whose occurrence was beyond doubt: almost every summer, there were cases of drowning in the river. After each disaster, a heavy mourning would descend upon the town, and crowds would attend the funeral. But there was also time for joy. I remember the Torah dedication ceremony. I can see it now in my mind’s eye, six- or seven-year-old me, watching the Hasidim in costume, riding horses through a crowd of thousands in the Nowy Rynek square, while a klezmer band played Hasidic melodies. Even the Gentiles passing by understood that all the commotion was in honor of the Torah, and feelings of joy and celebration filled the air.

In contrast, Christian processions marched through the town, accompanied by the tolling of church bells. The fire brigade band led them, while the clergy recited Latin prayers under a canopy. If you stood by the road, it was customary to remove your hat. One Christian feast brought a week-long market by the Russian Orthodox church: Polish vendors in open tents called out their wares—icons, amulets, trinkets, and toys. Others carried music boxes operated by hand cranks, selling lottery envelopes drawn by colorful parrots standing on perches atop their boxes. One could win all kinds of household items, toys, and more. A small amusement park operated alongside motorized carousels run by boys, Poles, and Jews alike (including me). We joined in the merriment of thousands of peasants and townsfolk.

Of all the times I have described, the one I call the “Zionist period” was the most beautiful. It began with our Hashomer Hatzair activities. It was a time of soul searching, marked by pure idealism. When forced to cease these activities, we formed a secret Zionist club. Members included Salk Waksman, Apple Romk, Kocer Shimon, Raphin Leib, Havel Moshe, Rozka Gartner (now Viderman), Motla Kriger Garbovicz, and others whose names I cannot remember. Every week or two, one of us would read a lecture on Zionist founders, territorialism, or emancipation, followed by a debate. We invited lecturers from across the political spectrum, including Dr. Samuel Hovel of Poale Zion, Yoseph Marmelstein from Hashomer Hatzair, and Bonam Singer of the Revisionists.

Once, I read aloud a story I had written in installments, in Polish, about a Jewish boy who wandered from one country to another, enduring many disappointments along the way, until he reached the shores of Israel—the shores of hope. I called the boy Ben-Zion. To us, that name symbolized the romance of Zionism. But we weren’t always immersed in seriousness and debate. On Saturday nights, we would go out to socialize at parties (“bipka”) hosted by the Jewish girls.

After high school exams, we felt a void. We longed to let loose. And for a while, we left our morals behind. Our slogan was “eat, drink, and loosen your belt” (an old Polish saying). We spent our days at the beach or in swimming pools, and our nights in restaurants. After vacation, I went to Warsaw to study, living at the Jewish Academic House in Praga, across the Vistula River.

There was also a wide range of political activity there, from the far left to the right. Speakers came to give lectures, attended by both supporters and opponents. I recall a rally where the late Menachem Begin spoke with great passion. There was a majority of revisionist students, but also some opponents. After some heckling, the opposing sides nearly came to blows. Who could have known then, before World War II, before the Holocaust, before the War of Independence, what fate lay ahead for the man standing before us, speaking with such passion?

And yet, the drums of war drew closer to our borders. Calls for help came from Jewish refugees expelled from Germany—a warning to Polish Jews. Then a fire broke out in our town. I heard Church bells ringing, fire brigade sirens. Anxiety gripped the townspeople as the sky turned red, fearing the flames would reach their homes. Alas, the inferno soon reached ours.

Yaakov-Kopel Rabinowitz Esteron

Translated from Hebrew by his

granddaughter Ellie Esteron