Home » Brandet Shlomo

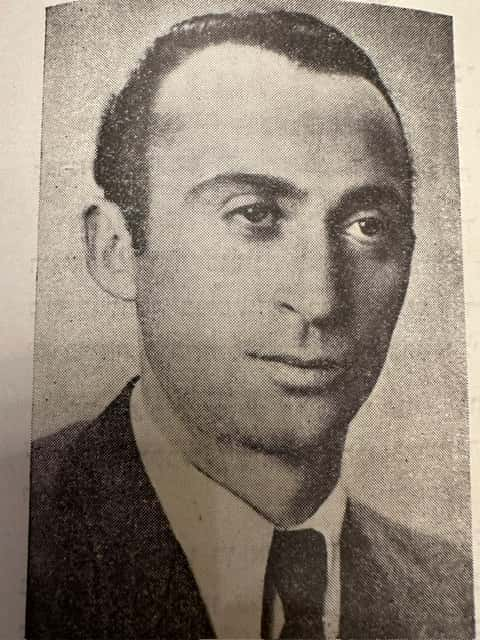

Shlomo Brandt was born to one of the wealthiest and most respected families in the town of Hrubieszów, to his parents Rachel and Yitzhak Brandt (of blessed memory). He was the fourth and youngest of the siblings: Yaakov (Yukel), Bluma, and Sima (all of blessed memory). Although the family was traditional, the children were educated in secular institutions.

Shlomo’s parents and his uncle, Shmuel Brandt, owned a flour mill that supplied flour to the Polish army.

At the age of 12, after meeting Ze’ev Jabotinsky during a visit he made to Hrubieszów, Shlomo joined the Betar movement and remained an active member. His older brother Yaakov was one of the leaders of the movement.

Shlomo was a strong and brave child who did not shy away from confronting non-Jews who mocked him, which often led to fights. In 1937, after a confrontation with a non-Jewish teacher at the gymnasium, Shlomo had to leave town and continued his studies in Vilna. In Vilna he remained active in Betar.

Shlomo was deeply impressed and influenced by Jabotinsky’s words during his visit to Vilna, in which he declared that no Jew would survive, and that those who could – must flee. Inspired by this, Shlomo worked to help young Jews escape from Poland, including by preparing forged documents. Those who managed to escape were saved and survived.

Before the war, Shlomo married Masha (née Berkovitz) from Vilna. Despite Jabotinsky’s advice to flee the ghetto, Shlomo stayed, as Masha’s family remained in Vilna. Masha had a twin sister, a milliner mother, and a wealthy businessman father.

Shlomo later admitted that although he feared for what awaited the Jews, he had no idea what the future would hold.

When the war broke out, Shlomo was involved in smuggling people to Warsaw using forged documents.

Shlomo recounted that he remained in the ghetto with his wife and her family and worked in maintenance for the Gestapo. This job protected him for a time. In the Vilna Ghetto, there were many Jews from various movements, including Hashomer Hatzair, among them Abba Kovner. A plan was developed in the ghetto to mount an uprising and use live weapons against the Germans, even though success was deemed unlikely. Still, there was a strong desire to revolt and kill as many Germans as possible.

During the War

In Vilna, Jews were told they would be divided into two ghettos. One contained about 29,000 Jews who were able-bodied and had work permits. The other, which was actually a transit camp leading to extermination, held about 11,000 Jews, mainly the elderly and sick who could not work. By the end of December 1941, the Jews in this second ghetto were killed at the Ponar execution site.

At Ponar, a site about 10 km south of Vilna, more than 75,000 people were murdered.

In the ghetto, Shlomo met the Jewish leader Kammermacher, who had significant connections in the Gestapo. These connections helped Shlomo and others during their time in the ghetto.

When Shlomo decided to escape to the forests and join the partisans, Kammermacher gave him useful items such as a compass and whistles, objects later donated to Yad Vashem. Kammermacher also gave Shlomo updated daily lists of Jews murdered at Ponar.

When people were taken from the ghetto under the pretense of labor but were being executed, Shlomo hid in a Gestapo building.

Due to having a unique permit exempting him from wearing the yellow star, Shlomo was able to leave and return to the ghetto for smuggling weapons and food.

Later, Shlomo learned that his mother had been shot to death, his brother was killed when he came to the aid of a friend who had been summoned for interrogation by the Gestapo, and his two sisters were drowned. His father, who survived until the end of the war, died from mental exhaustion.

In 1944, it seemed the war had ended in Vilna. Survivors felt the world had reopened. Communist partisans asked Shlomo to help locate Jewish survivors. He volunteered and traveled toward his hometown Hrubieszów and the nearby town of Zamość. To his shock, he found that the war still raged in the area and that Poles continued to hunt down and murder Jews.

On his journey, Shlomo was captured by two Poles who tried to lure him into a trap and kill him, but he managed to escape and injure his captors using a leather bag with metal corners. The bag had belonged to a Jew-murderer who had burned about 100 Jews alive. After killing the murderer, Shlomo kept the bag as a memento. He later used the sharp corners of the bag to defend himself. This bag was donated to Yad Vashem.

In the ghetto, Shlomo had helped smuggle Jews from the town to the forests. Eventually, he decided to join them. His friends urged him and his wife to stay, as their situation was relatively better. Fortunately, Shlomo did not succumb to that temptation. He reached the forest, only to later learn that the entire ghetto had been liquidated and no Jews remained alive.

Initially, only Jews participated in the partisan activity in the forests, but later Russian communists joined them as well.

As partisans, Shlomo and his comrades raided villages to steal food, sabotage German operations and collaborators, stole horses, metal tools, and anything that could be of use.

At the time, the Germans had been halted at the Russian front at the Battle of Stalingrad, which temporarily reduced their operations against the Jews.

Shlomo, his wife, her father, and his friends stayed in the forest until the Red Army liberated Vilna.

Shlomo led the Jewish partisans back to Vilna, joined by Russian partisans.

After the war, Shlomo received a commendation from the Soviets and was later appointed by them to manage a large brush factory.

Shlomo became active in the Aliyah Bet (illegal immigration to Palestine). He was involved in everything required to get refugees out of Europe, including forging documents.

In July 1946, after the war, a pogrom was carried out against Jewish survivors in Kielce, Poland, due to a blood libel. About 42 Jews were murdered, and 80 wounded. This demonstrated yet again that Jews were still in danger and had no future in Poland.

Although at the end of the war an order was issued by the Russians that no more Germans or collaborators were to be killed. Shlomo and his comrades continued to kill those they knew had taken part in murdering Jews, fearing that these war criminals would never face justice.

Immigration to Israel

As part of Aliyah Dalet (a continuation of Aliyah Bet), and despite many delays and obstacles, including attempts to harm Jewish refugees, Shlomo and his family passed through Czechoslovakia and arrived in Israel in 1947.

Shlomo and Masha Brandt settled in Givat Shmuel. Shlomo joined the Irgun n (also known as Etzel) and served in the IDF during several wars, including the Yom Kippur War. His pride was that both his sons, one of whom became a pilot, served in the IDF.

Shlomo and Masha Brandt had a remarkable family: two sons, seven grandchildren, and ten great-grandchildren, all living in Israel.