Home » Transports

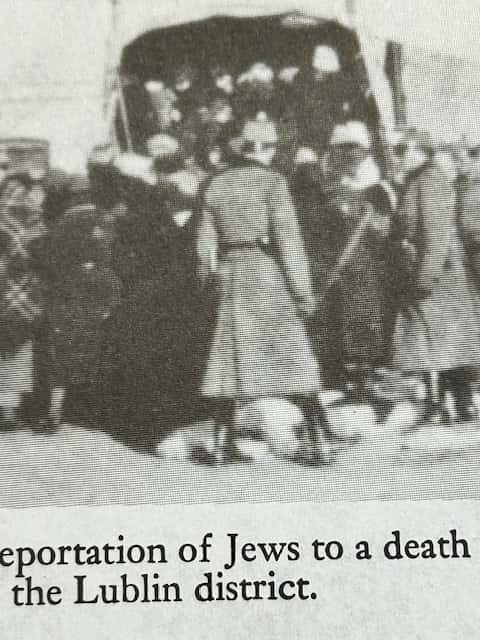

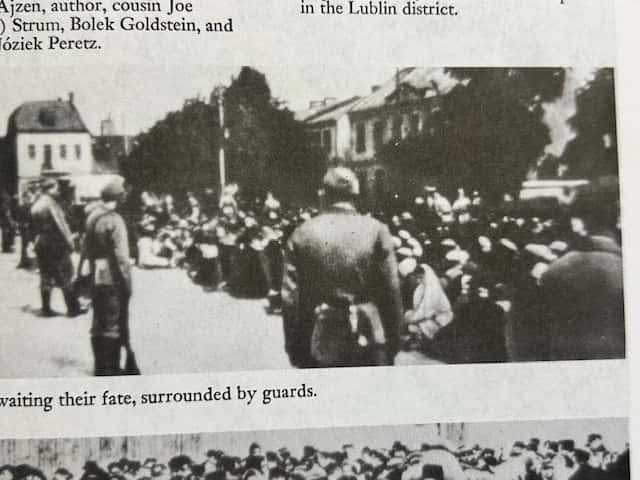

On August 13, 1940, the Germans, with the help of Polish policemen, sent about 600 Jews to a labor camp in Belzec. About half of them died of starvation or disease. In the summer of 1942, the Germans informed the Judenrat that they intended to send the Jews of Hrubieszow to work in the Pinsk region. In early June, the Germans, helped by Polish policemen, rounded up 3,049 Jews who had assembled in the market square, loaded them onto freight cars, and deported them to the Sobibor extermination camp. Forty Jews who resisted were summarily shot. A few days later, the Germans removed hundreds more Jews from their homes. Many resisted deportation, and 180 of them were murdered in the Jewish cemetery. The rest, including Jews from nearby towns, were sent to Sobibor.

About 2,500 Jews remained in the Hrubieszow ghetto, and they were relocated to a smaller ghetto, not far from the Jewish cemetery, and forced to work in German factories. On October 28, 1942, most of the remaining residents of the small ghetto, which now had about 1,600 people, were deported to Sobibor. About 400 of the ghetto residents who resisted deportation were murdered in the cemetery. Only 160 young Jews remained in Hrubieszow, and they were interned in a labor camp and forced to clean the ghetto area and demolish the cemetery.

In September 1943, the labor camp was liquidated, and its prisoners were transferred to the Bodzin camp, near Krasnik. Few managed to escape to the forests.

For years upon years, I repressed the experiences and events I lived through. At times, looking back, I couldn’t believe that the things I now recount were actually real. Could it be, I asked myself, that a person can “live” through such experiences, endure them, and still remain human, after all?

Here, for the first time, I recount one of the most difficult “experiences”:

Through various means, I arrived in the town of Sokal. At that time, almost no Jews remained in Hrubieszow, the city I was born in. For several weeks, I wandered hopelessly and aimlessly around Sokal, a refugee fearing what was to come.

One sunny day (which was rather cloudy), about two thousand men and women residing in Sokal, as well as survivors from Hrubieszow, like myself, and from the surrounding areas, were led to the train station, about two kilometers from the city.

We were all pushed into train cars. Once one of the cars was filled to capacity, leaving no room to move, others were crammed into another car. We stood at the station for an entire day. What happened inside the car was unspeakable. We all knew that our destination was Belzec – and that this was a one-way journey to our deaths.

I decided to fight for my life. I did everything I could to get closer to the window. Together with a few other determined young men, like myself, we resolved not to give in, no matter what. The train started moving. Working together and gathering all of our strength, we managed to dislodge and bend the bars and wire mesh that covered the window, and continued working until we had created an opening large enough to slip through. I knew full well that at the back of the car, on the steps, sat an armed German soldier with a submachine gun, ready to shoot at any moment.

I turned, carefully slid my body out, and jumped. I breathed in the fresh air. I was free again. I will never forget that night. It was October of 1942, and the night sky was pitch black. I fell into a ditch separating the railway from the parallel road and was injured.

After a few moments, I recovered and regained my bearings. That very night, I swam across a river, and made my way back to the Sokal ghetto. Sometimes, it seems to me that maybe, just maybe, it was all a dream I had. Could it really be true that I jumped from a moving train, and survived?